Thomas Edsall had a column about threats to democracy, particularly in the United States. He suggested that the problem wasn't just elite behavior, but also declining popular support for democratic institutions, and quoted various experts on why that might be happening. One idea that several proposed was that the public was reacting to failures of economic policy. According to Daron Acemoglu, an economist: "both center-right and center-left politicians promised huge gains from globalization and technology for everybody, and aspirations rose. And many groups were disappointed and frustrated with either slow or sometimes no economic progress." Jack Goldstone, a sociologist: "more rigid and culturally divided inequality breeds resentment of the elites. And I would say the elites brought this on themselves, by creating meritocratic bubbles that demean those outside and access to which they increasingly control for their own families. The elites have implemented policies of globalization, meritocracy and market-driven morals ... while ignoring the widespread harm these policies have done to many millions of their fellow citizens." And Elizabeth Suhay, a political scientist: "elites are an indirect cause of the rise of authoritarian parties. The neoliberal policies they have championed have led to increased inequality, stagnating wages and a weaker safety net for most citizens. Economic distress, pessimism and precarity increase citizens’ interest in radical political candidates and policies on both sides of the political aisle." The common theme is that the prevailing policies have been good for elites but not for the general public, so ordinary people turned against, not only those policies, but the elites who had pushed them.

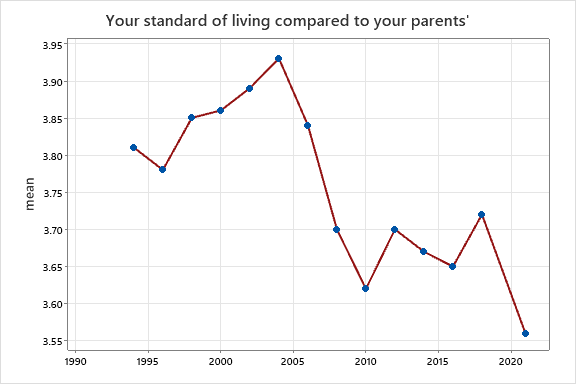

The common assumption behind these accounts is that people have become discontented with their general economic prospects: that they don't feel like they're making progress, or are making progress in the future. Is this true? There are lots of survey questions about current economic conditions, but not as many on general evaluations of your life. However, the General Social Survey has included this one since 1994: "Compared to your parents when they were the age you are now, do you think your own standard of living now is much better, somewhat better, about the same, somewhat worse, or much worse than theirs was?" The means*, counting "much better" as 5, "somewhat better" as 4, and so on:

It generally rose until the early 2000s, and then declined. It started falling before the "Great Recession" and never really bounced back--in 2018, it was only slightly above the 2008 level. (It hit a low in 2021, but that could reflect disruptions of life caused by the pandemic.

Breaking it down by some demographic groups:

In the 1990s, non-graduates had slightly more positive assessments than college graduates, but they have fallen behind since the early 2000s.

No clear difference between men and women in terms of the changes.

Also no clear difference by race.** There's a good deal of sampling variation in the estimates for blacks, so it's hard to say about short-term changes. But there's no general tendency for one group to pull ahead of the other.

There are differences by age group. Despite what people often say, it's was the older age groups that saw themselves slipping: in 2018, people aged 25-39 were more likely to see themselves as ahead of their parents than people aged 25-39 had been in 1994 and 1996. The assessments of young people became considerably more negative in 2021, but again that could be a short-term reaction to the pandemic.

These results support the accounts given above in two respects: there's been a general decline in the 21st century that doesn't track immediate economic conditions, and it's been more pronounced among less educated people. But if you look at the values on the y-axis, they are all well above 3.0: that is, in all groups at all times, the prevailing opinion is that their life is better than their parents was at the same age. For example, in 1994-2000, 65% of people without college degrees said that they were ahead of their parents' standard of living and only 13% said that they were below. In 2010-21, that had slipped to 59% ahead and 15% below, but that's still a solid margin on the optimistic side. The changes are also pretty small--there have been occasional questions about expectations for the next generation, and those have shown much larger changes. So overall, I think that there is an anti-elitist mood today, and it often shades into an anti-democratic mood, but I don't think that it results from dissatisfaction with one's own economic situation.

*All of the figures are limited to people born in the United States.

**I just show black and white--the number in other races is too small to be informative.