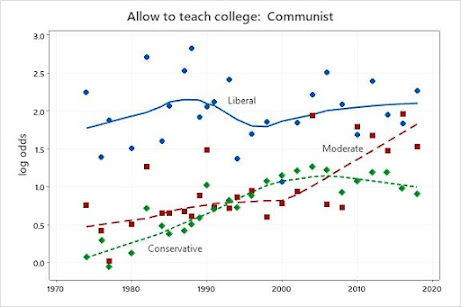

My last post discussed the relationship between tolerance and ideology, using an index of four questions from the General Social Survey on whether people with certain views should be allowed to teach in a university. It found that college-educated liberals were the most tolerant group, in the sense of believing that people with unpopular views should be allowed to teach, but that the gap had been getting smaller. In a comment on that post, Andrew Gelman suggested looking at each question individually, noting that two of the views could be considered left-wing (Communism and opposition to religion) while two could be considered right-wing (support military rule and belief that blacks are genetically inferior). That seemed reasonable, so I did it. The post and comment were a while ago, but I was on vacation, and forgot (or perhaps my unconscious mind decided) not to bring my computer, so I couldn't post anything. I restricted it to people with college degrees, since many people don't understand or have an idiosyncratic understanding of the terms "liberal" and "conservative." The GSS doesn't have a direct measure of understanding of the terms, but evidence from other surveys suggests it's closely related to education.*

Similar patterns for these three: moderates and conservatives became more tolerant while liberals stayed about the same, so that the ideological gap declined.

A different pattern: liberals became less tolerant starting in the early 1980s, while conservatives and moderates remained about the same until around 2010--since then, they have also become less tolerant.

How should these changes be interpreted? One possibility is that the ideological gap at the starting point was unusually large. The cultural conflicts of the 1960s may have made liberals especially conscious of free speech issues, so that the decline in the ideological gap since then is just a return to normal. Another possibility is that there was a change in liberal ideology, with a shift from emphasis on individual rights to an emphasis on inclusion--that is, not offending people. Observers who say that something like this is going on usually hold that it's a recent development, but these figures suggest that it started in the 1980s. That shouldn't be surprising--large changes in public opinion are usually gradual rather than sudden.

In any cases, views about the person who thinks that blacks are genetically inferior are clearly distinctive. It's interesting that both moderates and conservatives also became less likely to support the right of such a person to teach, starting in about 2010. Perhaps that's because conservatives were reacting against the charge that opposition to Obama (and later, support for Trump) was driven by racism.

*Andrew suggested looking at differences by party rather than ideology, which I think would be interesting but a separate issue.

No comments:

Post a Comment