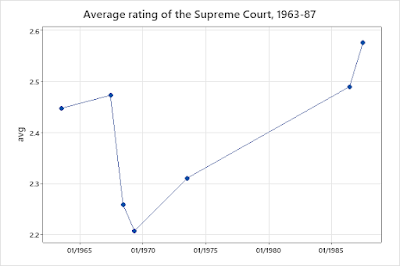

A comment on my last post noted that the Harris Poll question saying the Supreme Court had decided "that the police could not question a criminal unless he had a lawyer with him" was a mischaracterization--the decision just said that the police had to inform suspects of their right to have a lawyer present--and suggested that support might have been higher if the description had been accurate (saying "suspect" rather than "criminal" might also have made a difference). Shortly after the decision, the Gallup Poll asked "have you heard or read about the recent US Supreme Court decision about confessions by persons charged with a crime." If the respondent said yes, they asked "do you think the Supreme Court's ruling is good or bad?" Combining the two questions, the results were:

Hadn't heard: 58%

Good: 10%

Bad: 19%

Not sure: 13%

The comparison with the Harris Poll (which found that 30% approved, 56% disapproved, and 14% weren't sure) illustrates some general issues with interpreting surveys. You could argue that the Gallup results show that most people didn't really have an opinion on the Miranda decision--that most people who said they approved or disapproved in the Harris Poll were just giving an off-the-cuff response to the (inaccurate) description. On the other hand, you could say that there may also have been people who had heard about it but forgotten, and just needed a hint to jog their memory. Despite the differences, both surveys showed about the same ratio of negative to positive evaluations (almost 2:1): that is, they both suggested a widespread perception that the court was "soft on crime." You could imagine other questions that would tell you something about whether that perception could be changed--for example, what if you used a different description of the decision, or gave some background information, or asked people who said that they had heard of the decision what they thought that it said. One of the reasons that candidates commission their own surveys is to investigate things like that. The general point is that there's no definitive question that tells you what people "really think," and when you have several questions on a topic, you don't have to pick one as the best--they can all shed some light.

My recent posts on the Supreme Court got me wondering about how perceptions of the court have changed. Starting in 1986, a number of surveys, mostly by Gallup, have asked "do you think the Supreme Court has been too liberal, too conservative, or just about right" (with some minor variations in the introduction). The figures gives the percent saying too liberal minus the percent saying too conservative:

The different colors indicate Democratic and Republican presidents. There is a clear pattern in which people perceive the Court as too liberal when a Democrat is president and too conservative when a Republican is. This "thermostatic" reaction has been noted for other issues, but it's surprising that it appears for the Supreme Court. The last observation (September 2021) is an exception--despite a Democratic president, the perception of the court as conservative is even stronger than it was under Trump. The absence of a general trend is also interesting--most informed observers would say that the court has been getting more conservative over the period.

The percent who saw the court as "too liberal" or "too conservative" shows a different pattern--a pretty steady increase, without much difference between Democratic and Republican administrations. There isn't much change in the percent saying "about right," but the percent of "don't knows" has declined pretty steadily, from 15-20 percent in the 1980s to around 3 percent today. This change presumably reflects a combination of rising partisan polarization and increased attention to the Supreme Court.

[Data from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]