A few months ago, four economists writing in support of Jeb Bush's tax plan said we are experiencing "the weakest economic expansion since World War II." I was going to do a post on that subject, but didn't get around to it. I was reminded of the issue when Paul Krugman posted a figure showing better economic performance under Obama than under GW Bush. If Obama is the worst, how could Bush have been even worse?

The National Bureau of Economic Research provides dates of the beginning and end of recessions (an expansion is anything that's not a recession). Those go back to the 1850s, but modern data on GDP go back only to 1947, so I looked at recessions and expansions since then. The current expansion has indeed had the slowest average growth rate, breaking the record previously held by the 2002-7 expansion, which broke the record previously held by the 1991-2000 expansion. You may notice a pattern here. This is a scatterplot of average GDP growth in expansions since the late 1940s--the x axis is just a sequence number.

There's definitely a pattern there--the average growth keeps getting smaller. Hopefully that won't go on forever. The good news is that the average duration of expansions has tended to increase. The latest one, which started in the third quarter of 2009, is already longer than average, and is still going on. Another way to make the same point is to say that recessions are becoming less frequent.

But maybe Obama should have done better, since "recoveries tend to be stronger after deep recessions," according to the report I quoted above (p. 4). Here is a scatterplot of average quarterly growth by average quarterly growth in the preceding recession.

There's no clear relationship--you could call it a positive relationship with one glaring exception (the 2001-7 expansion), but "stronger recovery after a deep recession" implies a negative relationship. You could also define depth of the recession and strength of the recovery by the total growth (average times number of quarters), but no relationship is visible that way either.

So under Obama, it's been slow expansion, but almost all expansion (everything except the first quarter or two); with GW Bush, it was slow expansion and quite a bit of time in recession.

Tuesday, December 29, 2015

Thursday, December 24, 2015

Freedom of speech

Many democratic nations have laws against "hate speech." The United States does not--it's safe to say that the immediate reason is because the courts would strike them down as violating the first amendment, but I wondered if the difference in laws corresponded to a difference in public opinion? I couldn't find any questions specifically on "hate speech," but in 2006, the International Social Survey Programme asked about "people whose views are considered extreme by the majority. Consider people who want to overthrow the government by revolution. Do you think such people should be allowed to . . . hold public meetings to express their views" and "publish books expressing their views?" The choices were "definitely," "probably," "probably not," and "definitely not."

I summed the answers to the two questions, counting definitely as 4, probably as 3, etc. The average in the United States is 6.39--ie slightly more favorable than "probably." This was the highest value in the 33 nations surveyed, by a pretty substantial margin. The complete list:

6.39 “United_States”

6.02 “Portugal”

5.98 “Germany”

5.98 “Sweden”

5.97 “Switzerland”

5.93 “Philippines”

5.77 “Japan”

5.77 “Norway”

5.75 “Dominican_Republic”

5.69 “France”

5.66 “Venezuela”

5.65 “Taiwan”

5.65 “New_Zealand”

5.52 “Denmark”

5.52 “Israel”

5.48 “Canada”

5.48 “South_Africa”

5.39 “Uruguay”

5.32 “Slovenia”

5.27 “Croatia”

5.26 “Czech_Republic”

5.20 “Ireland”

5.06 “Netherlands”

5.04 “Finland”

5.00 “Australia”

4.94 “Chile”

4.91 “South_Korea”

4.91 “Great_Britain”

4.89 “Poland”

4.50 “Latvia”

4.28 “Hungary”

4.28 “Spain”

3.83 “Russia”

I summed the answers to the two questions, counting definitely as 4, probably as 3, etc. The average in the United States is 6.39--ie slightly more favorable than "probably." This was the highest value in the 33 nations surveyed, by a pretty substantial margin. The complete list:

6.39 “United_States”

6.02 “Portugal”

5.98 “Germany”

5.98 “Sweden”

5.97 “Switzerland”

5.93 “Philippines”

5.77 “Japan”

5.77 “Norway”

5.75 “Dominican_Republic”

5.69 “France”

5.66 “Venezuela”

5.65 “Taiwan”

5.65 “New_Zealand”

5.52 “Denmark”

5.52 “Israel”

5.48 “Canada”

5.48 “South_Africa”

5.39 “Uruguay”

5.32 “Slovenia”

5.27 “Croatia”

5.26 “Czech_Republic”

5.20 “Ireland”

5.06 “Netherlands”

5.04 “Finland”

5.00 “Australia”

4.94 “Chile”

4.91 “South_Korea”

4.91 “Great_Britain”

4.89 “Poland”

4.50 “Latvia”

4.28 “Hungary”

4.28 “Spain”

3.83 “Russia”

What I find most interesting is that the US and other countries with a British heritage don't have much in common, in contrast to views on inequality. That is, relatively high support for the rights of "extremists" is not part of some general cultural heritage, but something distinctive to the United States, presumably attachment to the Constitution, and especially the Bill of Rights. Another striking point is the difference between Portugal (second most favorable) and Spain (second least favorable). I wonder if it has to do with the way that they emerged from dictatorships in the 1970s? In Portugal, it was a revolution, or at least a coup--the dictatorship was forced out of office. As a result, "revolution" may have a favorable sound. In Spain, the transition was guided by a constitutional monarch.

Thursday, December 17, 2015

Trump, Perot, and Wallace

Back in August, I said that Donald Trump's appeal was similar to Ross Perot's in 1992: it was based on economic nationalism. Another view, which seems to be gaining in popularity, is that his appeal is based on racial and ethnic prejudice--comparisons to fascism are popular, but you could also look to what Geoffrey Wheatcroft calls the "long and unlovely American tradition of know-nothing bigotry and nativism." George Wallace would be an example.

[Source: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]

The difficulty in distinguishing these interpretations is that economic nationalism, and particularly opposition to immigration, could be a disguised form of racial and ethnic prejudice. Although surveys show a substantial decline in straightforward expressions of prejudice, many social scientists say that the underlying attitude is still there--people just don't reveal it as directly. In effect, saying that you're against "illegal immigration" is an acceptable way of indicating that you're against non-whites.

A 2011 survey by the Public Religion Research Institute included a number of questions on immigration which shed some light on the issue. One asked people if they agreed or disagreed that "We should make a serious effort to deport all illegal immigrants back to their home countries." 53% said that they completely or mostly agreed. It also asked how well various statements described immigrants coming to the United States today. 85% said that the "they are hardworking" described them very well or somewhat well, and 79% said that "they have strong family values" described them very well or somewhat well. Opinion was less favorable on two other qualities: 45% said "they make an effort to learn English" described most immigrants very well or somewhat well and 71% said that "they mostly keep to themselves" described them very well or somewhat well. Still, the comparison shows that hard-line views on illegal immigration don't necessarily reflect negative views of immigrants.

You can also look at support for deportation among different groups. It was highest among non-Hispanic whites (56%), but not that much lower among blacks (42%), Asian-Americans (46%), people of mixed race (56%), and "other" (47%). Even among Hispanics, there was significant support (24%).

I think these results count against the idea that a call for general deportation of illegal immigrants is primarily a coded appeal to racial prejudice. They also raise a question of why Trump is the only candidate who advocates (at least so far) a fairly popular position. The main reason is probably that people who have been involved in policy-making regard it as totally impractical--it's not just that it would involve enormous numbers of people, but many families include minor children who are citizens, it would complicate foreign relations, have negative effects on the economy...... Plus there would undoubtedly be many sympathetic individual cases--people who had been in the United States for most of their lives, were well-liked by their neighbors, were to ill to travel safely, etc. As a result, a policy of mass deportation might not remain popular if it were implemented. As an outsider, Trump isn't restrained by these kind of considerations.

So I'd continue to put Trump closer to Perot than to Wallace. Or maybe I should say "Trump supporters"--Trump the man is one of a kind, as he would be the first to tell you.

[Source: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]

Thursday, December 10, 2015

Greater America?

This post was inspired by the "is Donald Trump a fascist?" debate. I think that trying to define the essence of fascism is a pointless exercise, but like a lot of pointless exercises, it's hard to resist. If I were to give a definition, one of the key features would be irredentism: the belief that one's nation has a historical and/or cultural right to some territory that is currently part of another country.

That reminded me that a Pew survey from 2002 which I've written about before asked people for their views on the statement "There are parts of neighboring countries that really belong to [survey country]." The options were strongly agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree, and strongly disagree. About 13% said "don't know"; rather than treating those as missing values, I regarded them as a form of disagreement--in effect, "not as far as I know." To simplify things, I reduced the answers to agree and disagree plus don't know.

In the United States, 29% agreed. That was 38th of 42 nations in the sample--only Kenya, Ukraine, France, and Canada were lower. Still, it was higher than I expected--given the geographical location of the United States and its history of expansion, it's hard for me to imagine what "parts of neighboring countries" people could be referring to. None of the questions in the survey illuminate this point, but I looked at what kinds of people were more likely to say yes. Education was an important factor: over 40% of people who were not high school graduates agreed, but only 13% of those with a graduate degree. Agreement was higher among conservatives, people who said that religion was more important in their lives, and people who said the government controls too much of our daily lives.

So far, this is starting to sound like it fits into the usual right wing plus disaffected working class account of Trump supporters. Maybe they would respond to a call for "fifty-four forty or fight"? But there are some discordant findings. Racial/ethnic differences are small, but agreement is higher among blacks and Hispanics than among whites. People who agreed that the government had a responsibility to take care of poor people who couldn't take care of themselves were more likely to agree. Views on a couple of questions suggesting alienation from the government (when something is run by the government, it's usually inefficient and wasteful and the government is run for the benefit of all the people) had little or no relation to views on whether their were parts of other countries that really belonged to us.

Rather than a hidden reservoir of irredentist sentiment, I suspect that the "agrees" represent a combination of historical ignorance and idiosyncratic answers (for example, I could imagine someone treating Guantanomo Bay as a reason to say yes).

[Data from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]

That reminded me that a Pew survey from 2002 which I've written about before asked people for their views on the statement "There are parts of neighboring countries that really belong to [survey country]." The options were strongly agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree, and strongly disagree. About 13% said "don't know"; rather than treating those as missing values, I regarded them as a form of disagreement--in effect, "not as far as I know." To simplify things, I reduced the answers to agree and disagree plus don't know.

In the United States, 29% agreed. That was 38th of 42 nations in the sample--only Kenya, Ukraine, France, and Canada were lower. Still, it was higher than I expected--given the geographical location of the United States and its history of expansion, it's hard for me to imagine what "parts of neighboring countries" people could be referring to. None of the questions in the survey illuminate this point, but I looked at what kinds of people were more likely to say yes. Education was an important factor: over 40% of people who were not high school graduates agreed, but only 13% of those with a graduate degree. Agreement was higher among conservatives, people who said that religion was more important in their lives, and people who said the government controls too much of our daily lives.

So far, this is starting to sound like it fits into the usual right wing plus disaffected working class account of Trump supporters. Maybe they would respond to a call for "fifty-four forty or fight"? But there are some discordant findings. Racial/ethnic differences are small, but agreement is higher among blacks and Hispanics than among whites. People who agreed that the government had a responsibility to take care of poor people who couldn't take care of themselves were more likely to agree. Views on a couple of questions suggesting alienation from the government (when something is run by the government, it's usually inefficient and wasteful and the government is run for the benefit of all the people) had little or no relation to views on whether their were parts of other countries that really belonged to us.

Rather than a hidden reservoir of irredentist sentiment, I suspect that the "agrees" represent a combination of historical ignorance and idiosyncratic answers (for example, I could imagine someone treating Guantanomo Bay as a reason to say yes).

[Data from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]

Saturday, December 5, 2015

Two curves

As I said in my last post, most discussions of the "Phillips curve" consider the relationship between unemployment and prices, but Phillip's idea (which is a straightforward application of supply and demand reasoning) implies a relationship between unemployment and real wages. Of course, the two are related, because the change in real wages is the difference between the change in money wages and change in the price level. I calculated the equilibrium values of the annual rate of change in both for different levels of unemployment (see note 1 at the end for details):

unemp Inflation Wages Difference

3.5% 4.1% 5.6% 1.5%

4.0% 3.6% 5.0% 1.4%

4.5% 3.2% 4.4% 1.2%

5.0% 2.9% 4.0% 1.1%

5.5% 2.7% 3.7% 1.0%

6.0% 2.5% 3.4% 0.9%

6.5% 2.3% 3.1% 0.8%

7.0% 2.1% 2.9% 0.8%

7.5% 2.0% 2.8% 0,8%

There's a good deal of uncertainty about the exact numbers, but the general pattern is that growth in real wages is substantially higher when unemployment is lower (the median unemployment rate in the US since the late 1940s is about 5.6%, and about 85% of the values fall in the range shown above). So the "cost" of low inflation is not just higher unemployment, but slower growth in real wages.

Note: the price and wage data are monthly. The change in prices in a given month can be predicted pretty well by regressing it on the change in prices in each of the last 12 months and the change in money wages in each of the last four months. The change in wages can be predicted by change in prices in each of the last twelve months and the current inverse of the rate of unemployment. Unemployment doesn't directly affect prices, but it affects them indirectly through wages. I used the coefficients from those two regressions with a given rate of unemployment to get the figures above.

Tuesday, December 1, 2015

The Curve Nobody Knows

Recently there has been a lot of discussion of the "Phillips curve" in the media. It's usually described as involving the relationship between unemployment and inflation. Phillips actually wrote about the relationship between unemployment and wages, but even people who remember that treat the step from an increase in wages to an increase in the general price level as automatic. For example, Justin Wolfers says "lower unemployment would yield higher wage growth and hence higher inflation."

What difference does it make? Here's a regression of change in the consumer price index (inflation) on change in the consumer price index last year and 1/unemployment (the time span is 1948-2015):

inf= -0.25+0.75*inf(-1)+6.4*(1/unemp)

The estimate for 1/unemployment is not significantly different from zero (t=1.3).

Here's a regression of change in wages on change in the CPI last year and 1/unemployment:

winf= -0.97+.54*inf(-1)+18.3*(1/unemp)

The estimate for 1/unemployment is significantly different from zero (t=3.5).

I used change in manufacturing wages because that has been collected for the whole period. A broader measure of change in wages (private, non-supervisory) is available starting in 1964. The results:

winf= -1.25+.58*inf(-1)+17.8*(1/unemp)

The estimated effect of unemployment is almost the same and the t-ratio is actually larger.

Finally, what about the "hence" connecting wage increases and inflation?

inf= 0.57+0.54*inf(-1)+0.26*winf(-1)

So only a fraction of wage increases get passed through to price increases. The primary result of low unemployment is higher real wages, as Phillips suggested. Oddly, this point seems to have been forgotten as more sophisticated models were developed.

Phillips's opening sentences were: "When the demand for a commodity or service is high relatively to the supply of it we expect the price to rise . . . . Conversely when the demand is low relatively to the supply we expect the price to fall . . . . It seems plausible that this principle should operate as one of the factors determining the rate of change of money wage rates, which are the price of labour services." That is, he was talking about about relative prices, not the price level. If the "commodity or service" is used to produce other goods and services, there will be some spillover into the general price level, but it won't wipe out the change in relative prices. In the case of the "price of labour," a given amount of labor can be exchanged for more goods--real wages will rise.

What difference does it make? Here's a regression of change in the consumer price index (inflation) on change in the consumer price index last year and 1/unemployment (the time span is 1948-2015):

inf= -0.25+0.75*inf(-1)+6.4*(1/unemp)

The estimate for 1/unemployment is not significantly different from zero (t=1.3).

Here's a regression of change in wages on change in the CPI last year and 1/unemployment:

winf= -0.97+.54*inf(-1)+18.3*(1/unemp)

The estimate for 1/unemployment is significantly different from zero (t=3.5).

I used change in manufacturing wages because that has been collected for the whole period. A broader measure of change in wages (private, non-supervisory) is available starting in 1964. The results:

winf= -1.25+.58*inf(-1)+17.8*(1/unemp)

The estimated effect of unemployment is almost the same and the t-ratio is actually larger.

Finally, what about the "hence" connecting wage increases and inflation?

inf= 0.57+0.54*inf(-1)+0.26*winf(-1)

So only a fraction of wage increases get passed through to price increases. The primary result of low unemployment is higher real wages, as Phillips suggested. Oddly, this point seems to have been forgotten as more sophisticated models were developed.

Monday, November 23, 2015

Postscripts

1. On Sunday, the New York Times had a piece by Alec MacGillis called "Who Turned My Blue State Red?" on the question of why poor states vote Republican. I started reading it with low expectations, but perked up when I read "the people who most rely on the safety-net programs secured by Democrats are, by and large, not voting against their own interests by electing Republicans. Rather, they are not voting, period."

Those of us who are interested in politics tend to forget that a lot of people, and probably a majority of working class people, don't vote even in Presidential elections. In a post last year, I suggested that working-class turnout might have declined in states like West Virginia because of the decline of manufacturing and mining, so the people who continued to vote would be the local middle class. Although they might have relatively low incomes by national standards, they would compare themselves to the local people who didn't have steady jobs. From that perspective, they could be drawn to the Republicans, and especially sympathetic to the idea that poor people got that way because they made bad choices: they could think of examples from personal experience.

MacGillis seemed to be saying pretty much the same thing. He basically took the traditional journalist's approach of going out and talking to people--he offered some survey evidence, but it seemed sort of tangential. But it makes me think that someone should look at changes in the relationship between class and turnout by state.

2. In my last post, I talked about the relationship between height, weight, and earnings for men and women. The obvious way to do it would have been to look at the relationship between body mass index (weight over height squared) and earnings. I thought about doing it, but didn't want to to impose a constraint on the form of the relationship. But then I realized that I had wound up imposing a constraint on the relationship anyway, so why not try it? BMI turns out to be almost uncorrelated with height, so you can just look at the bivariate relationship between BMI and earnings. I rounded BMI to the nearest whole number, took mean earnings, and smoothed the figures to reduce the influence of sampling error, producing:

There are some interesting and unexpected things here:

1. There is a penalty for having a high BMI, but it's not much different for men and women.

2. Contrary to what I thought based on the figures in the previous graph, women do not benefit from being thin. Predicted income is about the same in the whole "normal" range (actually a little higher in the upper reaches, although I don't think the difference is large enough to be worth taking seriously).

3. Men suffer a substantial loss from being "underweight." That does match the results from my previous post.

Putting it together, it looks like men are the ones who lose the most if they don't have the "ideal" body. I don't really believe this--the numbers of men with low values of BMI are small, so I suspect that most or all of the apparent difference is just chance variation. But it's worth considering.

Those of us who are interested in politics tend to forget that a lot of people, and probably a majority of working class people, don't vote even in Presidential elections. In a post last year, I suggested that working-class turnout might have declined in states like West Virginia because of the decline of manufacturing and mining, so the people who continued to vote would be the local middle class. Although they might have relatively low incomes by national standards, they would compare themselves to the local people who didn't have steady jobs. From that perspective, they could be drawn to the Republicans, and especially sympathetic to the idea that poor people got that way because they made bad choices: they could think of examples from personal experience.

MacGillis seemed to be saying pretty much the same thing. He basically took the traditional journalist's approach of going out and talking to people--he offered some survey evidence, but it seemed sort of tangential. But it makes me think that someone should look at changes in the relationship between class and turnout by state.

2. In my last post, I talked about the relationship between height, weight, and earnings for men and women. The obvious way to do it would have been to look at the relationship between body mass index (weight over height squared) and earnings. I thought about doing it, but didn't want to to impose a constraint on the form of the relationship. But then I realized that I had wound up imposing a constraint on the relationship anyway, so why not try it? BMI turns out to be almost uncorrelated with height, so you can just look at the bivariate relationship between BMI and earnings. I rounded BMI to the nearest whole number, took mean earnings, and smoothed the figures to reduce the influence of sampling error, producing:

There are some interesting and unexpected things here:

1. There is a penalty for having a high BMI, but it's not much different for men and women.

2. Contrary to what I thought based on the figures in the previous graph, women do not benefit from being thin. Predicted income is about the same in the whole "normal" range (actually a little higher in the upper reaches, although I don't think the difference is large enough to be worth taking seriously).

3. Men suffer a substantial loss from being "underweight." That does match the results from my previous post.

Putting it together, it looks like men are the ones who lose the most if they don't have the "ideal" body. I don't really believe this--the numbers of men with low values of BMI are small, so I suspect that most or all of the apparent difference is just chance variation. But it's worth considering.

Saturday, November 21, 2015

Too rich or too thin?

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, despite its ominous-sounding name, is just a survey focusing on health. It asks people for their height and weight. As a result of an example I used for a class, I started thinking about the relationship between weight and earnings. The BRFSS doesn't have a measure of individual earnings, but it has a question on family income, and for people who are single (never married) and employed, it seems safe to assume that income and earnings are usually very close. Since the BRFSS obtains very big samples, that still leaves over 20,000 cases. I controlled for gender, height and weight. For both height and weight, I included the original and its square and allowed both to differ by gender. The following figures show the predicted values for a range of weights at selected heights.

For women, being thinner goes with having a higher income. The relationship seems to flatten out at the lowest weights, but basically if your goal is to be rich (or at least reasonably well paid), you can't be too thin. For men, the relationship is different--the highest expected earnings are at the middle weights, and the penalty for being below the "ideal" weight is at least as large as the penalty for being above it. For example, at 6 feet, the highest predicted earnings are at a bit over 200 pounds, and the predicted values for a man who weighs 150 and a man who weighs 295 are about the same.

Although I was primarily interested in weight, I noticed that the influence of height also differs by gender. Women benefit from being taller through the whole range. but the predicted values for tall men (6'4") and fairly tall men (6') are almost identical.

I wouldn't put too much faith in the exact shape of the curves, since I didn't experiment much with alternative specifications, but the possibility that "underweight" men earn less is intriguing. I put "underweight" in quotes because men who are in what is officially classified as the "normal or healthy" range earn less than men who are in the "overweight" range and sometimes even the lower reaches of "obese."

Thursday, November 12, 2015

Coulda been a contender

A few days ago, the New York Times had a story called "Boxing is a brutal, fading sport. Could football be next?" It pointed out that boxing used to be very popular, but said "there came a time when the fight game’s hold on the American spirit began to loosen, when it stood widely condemned as plain brutal." As the title suggests, it went on to say that maybe the same thing was starting to happen to football.

I looked for questions about whether boxing should be banned, and found a number going back to the 1950s. Several gave a simple choice:

Banned Not DK

6/1955 39% 45% 16%

4/1962 37% 47% 16%

4/1963 41% 43% 16%

6/1965 43% 45% 12%

3/1981 23% 70% 7%

7/1997 19% 74% 7%

One in 1984 gave people a choice of banning only amateur boxing, only professional boxing, or banning both. 39% favored both, 8% favored banning one of them, and 50% said both should be allowed. In 1999, a Fox survey gave a choice between regulated better (42%), left alone (24%), or abolished altogether (24%).

Public opinion didn't turn against boxing in a straightforward sense--in fact, support for abolishing boxing was generally lower in the 1980s and 1990s. Or looking at it another way, boxing's hold on the American spirit wasn't secure even in its glory days: about 40% wanted it abolished.

There are no questions about whether football should be abolished, but several in the past few years have asked if the respondent would allow a son to play football: about 70-75% say they would. People do seem to be aware of the dangers of football: in 2011, a survey asked "in which one of the following professional sports do you think athletes are most likely to sustain a permanent injury that will affect them after they retire?...NFL (National Football League) football, martial arts, boxing, hockey." More chose football (49%) than boxing (36%).

The lesson is that changes in the fortunes of the sports didn't directly reflect changes in public opinion. I think the basic reason that football flourished while boxing declined is that football developed an organization that could supply a consistent "product," and boxing never did.

[Source: iPOLL, Roper Center for Public Opinion Research. The Roper Center has moved from UConn, where it had been since 1977, to Cornell University. I'm sorry to see it go (I was interim director from 2004-6), but I'm glad that it found what promises to be a good home.]

I looked for questions about whether boxing should be banned, and found a number going back to the 1950s. Several gave a simple choice:

Banned Not DK

6/1955 39% 45% 16%

4/1962 37% 47% 16%

4/1963 41% 43% 16%

6/1965 43% 45% 12%

3/1981 23% 70% 7%

7/1997 19% 74% 7%

One in 1984 gave people a choice of banning only amateur boxing, only professional boxing, or banning both. 39% favored both, 8% favored banning one of them, and 50% said both should be allowed. In 1999, a Fox survey gave a choice between regulated better (42%), left alone (24%), or abolished altogether (24%).

Public opinion didn't turn against boxing in a straightforward sense--in fact, support for abolishing boxing was generally lower in the 1980s and 1990s. Or looking at it another way, boxing's hold on the American spirit wasn't secure even in its glory days: about 40% wanted it abolished.

There are no questions about whether football should be abolished, but several in the past few years have asked if the respondent would allow a son to play football: about 70-75% say they would. People do seem to be aware of the dangers of football: in 2011, a survey asked "in which one of the following professional sports do you think athletes are most likely to sustain a permanent injury that will affect them after they retire?...NFL (National Football League) football, martial arts, boxing, hockey." More chose football (49%) than boxing (36%).

The lesson is that changes in the fortunes of the sports didn't directly reflect changes in public opinion. I think the basic reason that football flourished while boxing declined is that football developed an organization that could supply a consistent "product," and boxing never did.

[Source: iPOLL, Roper Center for Public Opinion Research. The Roper Center has moved from UConn, where it had been since 1977, to Cornell University. I'm sorry to see it go (I was interim director from 2004-6), but I'm glad that it found what promises to be a good home.]

Friday, November 6, 2015

False consciousness in the donor class?

Paul Krugman recently had a column asking why Republicans claim that they will deliver faster economic growth, even though growth has actually been considerably faster under Democratic presidents since at least the 1940s. His answer is that it's partly "epistemic closure: modern conservatives generally live in a bubble into which inconvenient facts can’t penetrate" and partly that they "need to promise economic miracles as a way to sell policies that overwhelmingly favor the donor class." It seems to me that he's trying too hard to make a mystery out of this. I think Republicans promise faster growth because they believe they can deliver it, and they believe they can deliver it because they have a "common sense" argument that they can: there are tradeoffs between different goals, and if you insist on things like equality or environmental protection, you'll pay a price in economic growth. And in my experience, most people (probably all people most of the time) base their opinions on what seems like common sense to them rather than on careful analysis of the available data.

However, his column led me to wonder if the "donor class" actually does better under the Republicans, or if a rising tide lifts all boats, so that all income groups do better under the Democrats. I obtained data from the World Top Incomes Database on the average income (adjusted for price levels) of the bottom 90%, the 90-5 percent, the 95-99 per cent, and the top one percent. Then I did a regression with percent change over the previous year as the dependent variable and party of the president as the independent variable. The classification of years when party control changes is difficult: the president is inaugurated in January, so the new party is in control for the great majority of the year, but the American economy is big and there's a lot of inertia. So I counted those years as half one party and half the other.

The average annual change in real income under the two parties:

Dem Rep

0-90% 1.8% 0.0%

91-95% 2.0% 1.1%

95-99% 2.0% 1.2%

99-100% 2.0% 2.0%

The numbers in the World Top Incomes Database are pre-tax incomes, so it's likely that the top 1% really has done better under Republican presidents in terms of after-tax income.

However, his column led me to wonder if the "donor class" actually does better under the Republicans, or if a rising tide lifts all boats, so that all income groups do better under the Democrats. I obtained data from the World Top Incomes Database on the average income (adjusted for price levels) of the bottom 90%, the 90-5 percent, the 95-99 per cent, and the top one percent. Then I did a regression with percent change over the previous year as the dependent variable and party of the president as the independent variable. The classification of years when party control changes is difficult: the president is inaugurated in January, so the new party is in control for the great majority of the year, but the American economy is big and there's a lot of inertia. So I counted those years as half one party and half the other.

The average annual change in real income under the two parties:

Dem Rep

0-90% 1.8% 0.0%

91-95% 2.0% 1.1%

95-99% 2.0% 1.2%

99-100% 2.0% 2.0%

The numbers in the World Top Incomes Database are pre-tax incomes, so it's likely that the top 1% really has done better under Republican presidents in terms of after-tax income.

Saturday, October 31, 2015

See the happy extremist

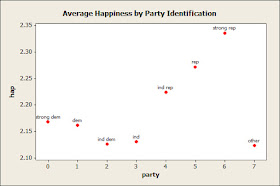

Since my series of posts on changes the relationship between political views and happiness trailed off into "something happened, but it's hard to say what it was," I wanted to do something that came to a definite conclusion. Arthur Brooks said "people at the extremes are happier than political moderates." He speculated that this was because "extremists have the whole world figured out, and sorted into good guys and bad guys. They have the security of knowing what’s wrong, and whom to fight." As you can see in this post, no such pattern is present in the GSS: average happiness increases as you go from left to right, except recently it's fallen off among people who say they are "extremely conservative." What if you look at happiness by party identification?

Now there is some pattern for strong identifiers to be happier (higher scores on the vertical axis). And since Democrats are more likely to be single, lower income, and less religious, controlling for those characteristics, as Brooks did, would make the pattern stronger. But what about the people who identify with another party? They're not a large group, even in the cumulative GSS, and are usually treated as missing values, but they are less happy than everyone except independents. And it seems likely that they are more "extreme" than any of the other groups--the two biggest enduring minor parties over the period have been the Libertarians and Greens. 14.7% of the "others" put themselves in one of the extreme ideological categories, higher than any other party group (11.3% of strong Republicans say they are extremely conservative and 1.0% say they are extremely liberal, for a total of 12.3%). And of course, there's a plausible explanation for why they would be less happy than Democrats or Republicans: they're dissatisfied with the way things are.

So it doesn't seem to be the case that extremists are happier than moderates. Rather, as I said a few posts ago, the pattern seems to be that people who are interested in politics are happier than people who aren't. Further evidence can be seen in the relationship with political views, people who answered "don't know" to the question on political ideology are the least happy group.

Brooks didn't give a link to his source, or any information about it, but if I were a betting man, I'd bet he did one of two things: (1) mixed up the patterns for party identification and ideology or (2) used a survey that counted "don't knows" on a liberal/conservative rating as moderates, which is sometimes done.

Now there is some pattern for strong identifiers to be happier (higher scores on the vertical axis). And since Democrats are more likely to be single, lower income, and less religious, controlling for those characteristics, as Brooks did, would make the pattern stronger. But what about the people who identify with another party? They're not a large group, even in the cumulative GSS, and are usually treated as missing values, but they are less happy than everyone except independents. And it seems likely that they are more "extreme" than any of the other groups--the two biggest enduring minor parties over the period have been the Libertarians and Greens. 14.7% of the "others" put themselves in one of the extreme ideological categories, higher than any other party group (11.3% of strong Republicans say they are extremely conservative and 1.0% say they are extremely liberal, for a total of 12.3%). And of course, there's a plausible explanation for why they would be less happy than Democrats or Republicans: they're dissatisfied with the way things are.

So it doesn't seem to be the case that extremists are happier than moderates. Rather, as I said a few posts ago, the pattern seems to be that people who are interested in politics are happier than people who aren't. Further evidence can be seen in the relationship with political views, people who answered "don't know" to the question on political ideology are the least happy group.

Brooks didn't give a link to his source, or any information about it, but if I were a betting man, I'd bet he did one of two things: (1) mixed up the patterns for party identification and ideology or (2) used a survey that counted "don't knows" on a liberal/conservative rating as moderates, which is sometimes done.

Friday, October 30, 2015

What is to be explained?

In my last post, I said that the relationship between political views and happiness changed over time and that I'd have to think before offering an explanation. My general idea was that political polarization had been growing, so that there was an increasing tendency for people to be less happy when the "wrong" party was in power. The only problem was that there were signs of a growth in polarization in the 1990s, like the 1994 congressional election and the impeachment of Bill Clinton, so why wasn't anything visible then? In the hope of getting a hint, I estimated the relationship between self-rated ideology and happiness by year, and got this:

Higher values mean a tendency for conservatives to be relatively less satisfied. The zero value is arbitrary--it just represents the pattern in 2014. The 95% confidence intervals for the annual estimates are about plus or minus .02 (about plus or minus .03 in the first half of the period), so you could not reject the hypothesis that all the values within the Bush or Obama presidencies were the same. However, if you just look at the figure, it looks more like just random variation with a few exceptions--2004, 2008 and 2010.

So maybe the problem isn't to explain the patterns under recent presidents, but the patterns in a few particular years? The GSS is conducted in March, and March 2010 was when the Affordable Care Act was passed. So maybe that explains why conservatives (and especially "extremely conservative" people) were relatively unhappy then, but (maybe) not in 2012 and 2014. With G. W. Bush, the 2002 pattern wasn't unusual, but 2004-8 were. Those years had something in common--the United States was engaged in an extended war. It seems plausible that liberals and moderates would be more worried about war and its implications. The GSS started in 1972, but didn't include the question on political views until 1974, so being at war was a new event in the history of the available data (the first Gulf War took place in January/Feb 1991, but American troops were already leaving by March).

I'm not sure that what needs to be explained is a few unusual years rather than presidencies--the point is just that it's another way to look at it, and the data doesn't let us decide between the possibilities. This is a case where we start with what seems like a lot of data--50,000 cases--which turns out to be a lot less than we need for some purposes.

Higher values mean a tendency for conservatives to be relatively less satisfied. The zero value is arbitrary--it just represents the pattern in 2014. The 95% confidence intervals for the annual estimates are about plus or minus .02 (about plus or minus .03 in the first half of the period), so you could not reject the hypothesis that all the values within the Bush or Obama presidencies were the same. However, if you just look at the figure, it looks more like just random variation with a few exceptions--2004, 2008 and 2010.

So maybe the problem isn't to explain the patterns under recent presidents, but the patterns in a few particular years? The GSS is conducted in March, and March 2010 was when the Affordable Care Act was passed. So maybe that explains why conservatives (and especially "extremely conservative" people) were relatively unhappy then, but (maybe) not in 2012 and 2014. With G. W. Bush, the 2002 pattern wasn't unusual, but 2004-8 were. Those years had something in common--the United States was engaged in an extended war. It seems plausible that liberals and moderates would be more worried about war and its implications. The GSS started in 1972, but didn't include the question on political views until 1974, so being at war was a new event in the history of the available data (the first Gulf War took place in January/Feb 1991, but American troops were already leaving by March).

I'm not sure that what needs to be explained is a few unusual years rather than presidencies--the point is just that it's another way to look at it, and the data doesn't let us decide between the possibilities. This is a case where we start with what seems like a lot of data--50,000 cases--which turns out to be a lot less than we need for some purposes.

Friday, October 23, 2015

Lost Happiness

This post is inspired by Andrew Gelman's comment on a previous post about partisanship and satisfaction with various things. Andrew noted that the relationship between partisanship and general happiness had changed, a point first noticed by Jay Livingston, who was commenting on a piece by Arthur Brooks entitled "Conservatives are Happier, and Extremists are Happiest of All." Brooks said "the happiest Americans are those who say they are either 'extremely conservative' . . . or 'extremely liberal' (35 percent). Everyone else is less happy, with the nadir at dead-center 'moderate' . . . ." He didn't give a source, but Livingston noted that in the 2010 sample of the General Social Survey, people who called themselves "extremely conservative" were the least happy group.

I looked at the complete GSS data starting in 1972 to see how the relationship changed. If you look at the combined sample, there's absolutely no sign that "extremists" are happier: happiness increases pretty steadily as you go from left to right. Brooks said he had controlled for a number of other variables, so maybe that accounts for it. I doubt it, but I'm not going to pursue that issue.

Next I allowed the relationship to change from year to year, expecting that there would be some gradual trend--a tendency for conservatives to become relatively less happy. There was no sign of that, but I thought I saw some variation that corresponded to party of the president--conservatives were relatively unhappy when Democrats were in office. But on including a set of dummy variables for presidents, there was little variation until GW Bush and then Obama. So I ended up with a three-period classification: up to 2000, Bush (2002-8--the GSS is done only in even numbered years), and Obama (2010-4). The relationship in the three periods is shown in this figure:

Higher numbers on the vertical axis mean happier. In the 20th century, conservatives were happier than liberals, with those who called themselves extremely conservative being happiest of all. Under Bush, conservatives and extreme conservatives stayed about the same, but everyone else became less happy. Under Obama, conservatives and extreme conservatives became less happy, but everyone else stayed about the same. The net result was that happiness went down across the board between the 20th century and Obama. Liberals and moderates lost under Bush and didn't gain under Obama, and conservatives didn't gain under Bush and lost under Obama. There seems to have been an especially large drop-off among extreme conservatives, who became a lot less happy under Obama.

I was surprised at these results--I thought that even among people with strong political views happiness would be influenced overwhelmingly by personal circumstances, so that any relationship with the party of the president would be so small as to be undetectable. And if it is influenced by the party of the president, why just since GW Bush? People had strong feelings about at least some of the 20th-century presidents, notably Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton. So I'm going to have to think about this before proposing an explanation.

I looked at the complete GSS data starting in 1972 to see how the relationship changed. If you look at the combined sample, there's absolutely no sign that "extremists" are happier: happiness increases pretty steadily as you go from left to right. Brooks said he had controlled for a number of other variables, so maybe that accounts for it. I doubt it, but I'm not going to pursue that issue.

Next I allowed the relationship to change from year to year, expecting that there would be some gradual trend--a tendency for conservatives to become relatively less happy. There was no sign of that, but I thought I saw some variation that corresponded to party of the president--conservatives were relatively unhappy when Democrats were in office. But on including a set of dummy variables for presidents, there was little variation until GW Bush and then Obama. So I ended up with a three-period classification: up to 2000, Bush (2002-8--the GSS is done only in even numbered years), and Obama (2010-4). The relationship in the three periods is shown in this figure:

Higher numbers on the vertical axis mean happier. In the 20th century, conservatives were happier than liberals, with those who called themselves extremely conservative being happiest of all. Under Bush, conservatives and extreme conservatives stayed about the same, but everyone else became less happy. Under Obama, conservatives and extreme conservatives became less happy, but everyone else stayed about the same. The net result was that happiness went down across the board between the 20th century and Obama. Liberals and moderates lost under Bush and didn't gain under Obama, and conservatives didn't gain under Bush and lost under Obama. There seems to have been an especially large drop-off among extreme conservatives, who became a lot less happy under Obama.

I was surprised at these results--I thought that even among people with strong political views happiness would be influenced overwhelmingly by personal circumstances, so that any relationship with the party of the president would be so small as to be undetectable. And if it is influenced by the party of the president, why just since GW Bush? People had strong feelings about at least some of the 20th-century presidents, notably Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton. So I'm going to have to think about this before proposing an explanation.

Saturday, October 17, 2015

Miscellany

1. In a post earlier this month, we saw that people who were less satisfied with their financial situation were more likely to be Democrats. Common sense suggests that the relationship will differ depending on income. By and large, Democrats favor higher taxes and more spending on social programs, while Republicans favor lower taxes and spending. The higher your income, the more you benefit from low taxes and the less you lose from cuts in social programs. So a high-income person who's dissatisfied with their financial situation stands to improve it by voting Republican. I looked for an interaction using the Pew data, but there wasn't much evidence of one. While I did this, I had the feeling that I'd done this before, probably several times, with the same lack of results.

So to remind myself, I'll write this down: even among people with high incomes, dissatisfaction with your financial situation goes with more support for the Democrats. Of course, people have lots of reasons for choosing one party over another, so what if we look more specifically at opinions on redistribution?

The General Social Survey has a question "So far as you and your family are concerned, would you say that you are pretty well satisfied with your present financial situation, more or less satisfied, or not satisfied at all?" and one that asks them to place themselves on a 7-point scale going from "the government in Washington ought to reduce the income differences between the rich and the poor, perhaps by raising the taxes of wealthy families or by giving income assistance to the poor [to] . . . the government should not concern itself with reducing this income difference between the rich and the poor." If you regress the opinions on redistribution on financial satisfaction and income, the estimate for financial satisfaction is -.317 (a negative sign means dissatisfaction goes with support for redistribution). If you break that down by income level, that's -.367 for people with family incomes of under $40,000, -.245 for people between $40,000 and $90,000, and -.119 for people with incomes of $90,000 and above. The pattern implies that there's some value of income above which the relationship would change direction, but even in the highest income group distinguished by the GSS ($150,000 and up), dissatisfaction goes with more support for redistribution.

2. In a post from 2013, I remarked that Barry Goldwater had been left out in an account of how the Republicans lost black voters. Then last week I saw a piece by Andrew Rosenthal which said "The Republicans moved way past conservatism long ago. .... Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush, even Ronald Reagan would be apostates in this Republican Party." That is, Goldwater is lumped in with two relatively moderate Republican presidents. As I said in my post, the memory of Goldwater seems to have mellowed--people don't recall how extreme he was. I don't know well he'd get along personally with the Republicans in Congress today, but his politics would fit right in.

3. I ran across an obscure article by Robert Solow. Of course, Solow is anything but obscure--Nobel winner in economics, former president of the American Economic Association, etc.--but this article has been cited only twice according to Google Scholar (it was a brief contribution to a symposium in honor of another economist). It contains some comments on econometric modelling (and by extension, quantitative analysis in the social sciences) that I found interesting:

"For all our fancy talk about testing hypotheses and estimating structural parameters, I think that econometric modelling has actually made very little progress in doing those profound things. . . . Instead, I think, the main function of econometric modelling is rather to provide very sophisticated descriptive statistics." He did not mean this as a criticism: "The important thought I want to get across is that there is nothing undignified about econometrics as descriptive statistics rather than hypothesis-testing."

So to remind myself, I'll write this down: even among people with high incomes, dissatisfaction with your financial situation goes with more support for the Democrats. Of course, people have lots of reasons for choosing one party over another, so what if we look more specifically at opinions on redistribution?

The General Social Survey has a question "So far as you and your family are concerned, would you say that you are pretty well satisfied with your present financial situation, more or less satisfied, or not satisfied at all?" and one that asks them to place themselves on a 7-point scale going from "the government in Washington ought to reduce the income differences between the rich and the poor, perhaps by raising the taxes of wealthy families or by giving income assistance to the poor [to] . . . the government should not concern itself with reducing this income difference between the rich and the poor." If you regress the opinions on redistribution on financial satisfaction and income, the estimate for financial satisfaction is -.317 (a negative sign means dissatisfaction goes with support for redistribution). If you break that down by income level, that's -.367 for people with family incomes of under $40,000, -.245 for people between $40,000 and $90,000, and -.119 for people with incomes of $90,000 and above. The pattern implies that there's some value of income above which the relationship would change direction, but even in the highest income group distinguished by the GSS ($150,000 and up), dissatisfaction goes with more support for redistribution.

2. In a post from 2013, I remarked that Barry Goldwater had been left out in an account of how the Republicans lost black voters. Then last week I saw a piece by Andrew Rosenthal which said "The Republicans moved way past conservatism long ago. .... Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush, even Ronald Reagan would be apostates in this Republican Party." That is, Goldwater is lumped in with two relatively moderate Republican presidents. As I said in my post, the memory of Goldwater seems to have mellowed--people don't recall how extreme he was. I don't know well he'd get along personally with the Republicans in Congress today, but his politics would fit right in.

3. I ran across an obscure article by Robert Solow. Of course, Solow is anything but obscure--Nobel winner in economics, former president of the American Economic Association, etc.--but this article has been cited only twice according to Google Scholar (it was a brief contribution to a symposium in honor of another economist). It contains some comments on econometric modelling (and by extension, quantitative analysis in the social sciences) that I found interesting:

"For all our fancy talk about testing hypotheses and estimating structural parameters, I think that econometric modelling has actually made very little progress in doing those profound things. . . . Instead, I think, the main function of econometric modelling is rather to provide very sophisticated descriptive statistics." He did not mean this as a criticism: "The important thought I want to get across is that there is nothing undignified about econometrics as descriptive statistics rather than hypothesis-testing."

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

Partisanship and Happy Marriages

In my last post, I mentioned the claim that Republicans report having happier marriages than Democrats. I said it was basically true, but didn't give details, so here they are. The General Social Survey question is "Taking things all together, how would you describe your marriage? Would you say that your marriage is very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?" Partisanship is measured by seven categories; strong Democrat, Democrat, independent leaning Democratic, Independent, Independent leaning Republican, Republican, strong Republican. The question has been asked pretty regularly since 1973. Combining all years, the pattern is like this (higher numbers mean happier):

So (married) Republicans are happier with their marriages than (married) Democrats. People with stronger political affiliation are happier than those with weaker ones, with pure independents the least happy. I wouldn't call the differences large, but they are real (the F-statistic with 6df in the numerator is about 27).

Does this pattern change over time? Probably a little, but the general shape remains the same. I broke the data into three periods of roughly equal length:

The most noticeable difference is that average reported happiness with marriage was higher in the first period. The party differences on Democrat to Independent side may have changed a little, but nothing much is visible on the Independent to Republican side.

Why do these differences exist? My idea is that some people are more inclined to be satisfied with things, and they'll be attracted to the party of the status quo (see my previous post). As for why independents are the least happy, I think it's because people who are fatalistic or cynical are less likely to be happy with things, and many independents or weak partisans are fatalistic or cynical--that is, they're basically not interested.

Note: I just got a call from the Ben Carson presidential campaign. Maybe they figure that since I'm happy with my marriage, I'm a good prospect.

Thursday, October 8, 2015

Haven in a heartless world

A couple of months ago, the New York Times reported on some research by W. Bradford Wilcox saying that Republicans are happier with their marriages than Democrats are. It's a bit more complicated than that, because strong Democrats and Republicans report being happier with their marriages than independents or weak partisans, but basically the claim is correct. But neither the article nor the original research asked whether this relationship was specific to marriage or part of a more general tendency. To investigate this, I used a 2005 Pew survey that asked people how satisfied they were with ten different aspects of their life. I considered correlations with both self-rated ideology and partisanship (independents were closer to Democrats than Republicans, so I gave them a score 3/4 of the way between the partisans). I list the items by average correlation: a positive number means that Democrats/liberals are more dissatisfied.

Ideo Party

Household income .153 .211

Standard of living .140 .202

Happy with life .139 .187

Your job .111 .152

Housing .109 .117

Free time .078 .081

Relationship with spouse .081 .079

Family life .054 .096

Relationship with parents .047 .037

Relationship with children .026 .052

Liberals and Democrats tend to be less satisfied with everything. Beyond that, the items fall into two groups: those involving material things are more strongly associated with ideology and party, while those involving family and free time are less strongly associated. So although the claim reported in the article was correct, it was misleading because it suggested that liberals and Democrats were dissatisfied with family life in particular. In fact, you could interpret it in the opposite way: for liberals and Democrats, the family provides (partial) relief from the world outside.

[Data from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]

Ideo Party

Household income .153 .211

Standard of living .140 .202

Happy with life .139 .187

Your job .111 .152

Housing .109 .117

Free time .078 .081

Relationship with spouse .081 .079

Family life .054 .096

Relationship with parents .047 .037

Relationship with children .026 .052

Liberals and Democrats tend to be less satisfied with everything. Beyond that, the items fall into two groups: those involving material things are more strongly associated with ideology and party, while those involving family and free time are less strongly associated. So although the claim reported in the article was correct, it was misleading because it suggested that liberals and Democrats were dissatisfied with family life in particular. In fact, you could interpret it in the opposite way: for liberals and Democrats, the family provides (partial) relief from the world outside.

[Data from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]

Saturday, October 3, 2015

More morals

The WVS also has questions about whether the following can ever be justified: "claiming government benefits to which you are not entitled," "avoiding a fare on public transport," "cheating on taxes," and "someone accepting a bribe." I wasn't going to write about those, but then Roger Cohen had a column in which he said that the Volkswagen emissions scandal reflected something about the German character. Specifically, "there is something peculiarly German about the chasm between professed moral rectitude and reckless wrongdoing." The WVS data, of course, are about what people say, not what they do, but that led me to wonder where Germans rank in "moral rectitude," which I would interpret as saying that breaking laws like those given above can never be justified.

I combined them into a scale and again plot it against the log of per-capita GDP (for those of you keeping score at home, it's based on the percent saying "never justifed" in each nation with weights from a principal component analysis). My expectation was that there would be two factors working in different directions. First, people in countries with higher levels of government corruption would be more likely to say that breaking those laws can be justified on the grounds that sometimes you have to. Second, more educated people would be less absolutist: they could imagine scenarios in which violating some rules would be justified. In general, more affluent countries have less governmental corruption and more educated populations.

Turkey is the biggest outlier, with very high rates of "never justified." It's the only predominantly Islamic country in the sample, which could be the explanation. If you put Turkey aside, then there is a tendency for people in more affluent nations to be more "absolutist." I could look up ratings for corruption, but my impression is that they would't correlate very highly with opinions. Germany is right in the middle on "professed moral rectitude." At the top are Turkey and Japan, with Italy (a surprise) in third, followed closely by Switzerland and the Netherlands.

I combined them into a scale and again plot it against the log of per-capita GDP (for those of you keeping score at home, it's based on the percent saying "never justifed" in each nation with weights from a principal component analysis). My expectation was that there would be two factors working in different directions. First, people in countries with higher levels of government corruption would be more likely to say that breaking those laws can be justified on the grounds that sometimes you have to. Second, more educated people would be less absolutist: they could imagine scenarios in which violating some rules would be justified. In general, more affluent countries have less governmental corruption and more educated populations.

Turkey is the biggest outlier, with very high rates of "never justified." It's the only predominantly Islamic country in the sample, which could be the explanation. If you put Turkey aside, then there is a tendency for people in more affluent nations to be more "absolutist." I could look up ratings for corruption, but my impression is that they would't correlate very highly with opinions. Germany is right in the middle on "professed moral rectitude." At the top are Turkey and Japan, with Italy (a surprise) in third, followed closely by Switzerland and the Netherlands.

Thursday, October 1, 2015

Morals

I concluded my last post by saying that Americans were relatively conservative on "moral" issues. This wasn't based on any specific piece of research, just an impression that I'd formed, so I did some more systematic analysis using the 2005-9 World Values Survey. The WVS has a series of questions about whether various things can "never be justified," "always be justified," or something in between. I constructed a scale based on opinions about homosexuality, prostitution, abortion, divorce, ending the life of an incurably ill person, and suicide. To limit the comparison to roughly similar nations, I used only nations in the OECD plus Taiwan. I show a scatterplot of scores (higher values mean more conservative) versus log of per-capita GDP.

As often happens, things are more complicated than I had remembered them. The United States is indeed conservative relative to its economic development (or something that's highly correlated with economic development, perhaps education), but it's not as exceptional as I'd thought. The biggest outlier is Italy. You could say that's because of the historical influence of the Catholic church, but Spain is also in the sample and it doesn't stand out at all. But for whatever reason, Italy stands out. Since my last post was an attempt to explain the nature of American conservatism, this suggests that if I'm right, there should be similarities to Italian conservatism. I know very little about recent Italian conservatism, but given the example of Silvio Berlusconi, I hope I'm wrong.

As often happens, things are more complicated than I had remembered them. The United States is indeed conservative relative to its economic development (or something that's highly correlated with economic development, perhaps education), but it's not as exceptional as I'd thought. The biggest outlier is Italy. You could say that's because of the historical influence of the Catholic church, but Spain is also in the sample and it doesn't stand out at all. But for whatever reason, Italy stands out. Since my last post was an attempt to explain the nature of American conservatism, this suggests that if I'm right, there should be similarities to Italian conservatism. I know very little about recent Italian conservatism, but given the example of Silvio Berlusconi, I hope I'm wrong.

Saturday, September 26, 2015

Towards a general theory of crankification, part 2

I promised a post on why conservatism has become a "cause." An immediate factor is opposition to President Obama. Some people would say that's because he's black, but I think that's no more than a secondary factor. The primary factor is that a lot of people were excited about him, and he seemed to have some kind of vision. That's pretty unusual--the last nominee who it was true of was probably Reagan, and before him I guess McGovern, who didn't come close to winning. I believe that in a debate with Hillary Clinton, Obama referred to Reagan as a "transformative" president, in contrast to Bill Clinton, and said that he wanted to be more like Reagan in that respect. I also recall that Hillary seemed puzzled, not quite sure what he meant. But conservatives knew what he meant, or thought they did: he wanted to be the anti-Reagan. (I think that that was a misreading and he actually had something more like a "beyond left and right" aspiration).

But there's also a long-term component: this is something that's been developing over decades. If conservatism is basically defense of the status quo, you'd expect it to have the central institutions of society on its side. Historically, that's usually been the case. But in the 1960s-70s, prevailing political views at universities (especially elite ones) went from being mostly moderate or slightly conservative to being overwhelmingly on the left. A similar development happened with newspapers and magazines, especially "quality" ones, although it didn't go as far. That's one reason that conservatives feel embattled--they have a sense a sense that an important part of the "establishment" is against them. Universities are especially important, since young adulthood is when many people start getting interested in politics.

The limitation of this explanation it doesn't explain why contemporary American conservatism is particularly ideological by international standards. Although I don't have good data, I think the shift of higher education to the left is a widespread phenomenon, and in many countries universities have traditionally been centers of radical politics. I think that the answer may be that, compared to other nations, Americans are conservative on a lot of "moral" beliefs. For example, although the United States has a high divorce rate, Americans are less likely to approve of divorce than people in almost all other affluent nations (which reminds me that I should have a post on that subject). The social changes of the 1960s and 1970s haven't been rolled back, and in some ways have continued to go on with no signs of stopping: for example, growing acceptance of gays and lesbians. I think this is why American conservatives continue to feel embattled even though the last 30 years have been a fairly conservative period in other ways.

Being embattled means that people are going to stick together, and work harder to justify their views. The left was traditionally sustained by a sense that elites were against them, but the common people were (at least potentially) on their side; now that feeling is also found on the right.

But there's also a long-term component: this is something that's been developing over decades. If conservatism is basically defense of the status quo, you'd expect it to have the central institutions of society on its side. Historically, that's usually been the case. But in the 1960s-70s, prevailing political views at universities (especially elite ones) went from being mostly moderate or slightly conservative to being overwhelmingly on the left. A similar development happened with newspapers and magazines, especially "quality" ones, although it didn't go as far. That's one reason that conservatives feel embattled--they have a sense a sense that an important part of the "establishment" is against them. Universities are especially important, since young adulthood is when many people start getting interested in politics.

The limitation of this explanation it doesn't explain why contemporary American conservatism is particularly ideological by international standards. Although I don't have good data, I think the shift of higher education to the left is a widespread phenomenon, and in many countries universities have traditionally been centers of radical politics. I think that the answer may be that, compared to other nations, Americans are conservative on a lot of "moral" beliefs. For example, although the United States has a high divorce rate, Americans are less likely to approve of divorce than people in almost all other affluent nations (which reminds me that I should have a post on that subject). The social changes of the 1960s and 1970s haven't been rolled back, and in some ways have continued to go on with no signs of stopping: for example, growing acceptance of gays and lesbians. I think this is why American conservatives continue to feel embattled even though the last 30 years have been a fairly conservative period in other ways.

Being embattled means that people are going to stick together, and work harder to justify their views. The left was traditionally sustained by a sense that elites were against them, but the common people were (at least potentially) on their side; now that feeling is also found on the right.

Sunday, September 20, 2015

Towards a general theory of crankification

In the Republican primary, almost all of the candidates are presenting themselves as committed conservatives. The one clear exception is the one who's surprised everyone by jumping into first place and staying there. Under those circumstances, you'd expect some of the others to emulate him, not by taking exactly the same positions, but by deviating from orthodoxy on some things and cultivating an image of someone who says what he thinks and doesn't care about labels. But there's no sign that anyone's doing that.

Paul Krugman notices the same phenomenon, which he calls "crankification." The term is a bit unfair--it might be more accurate to call it something like "convergence on extreme positions." It's not surprising that a Republican would want to cut income taxes on high incomes, as Jeb Bush's plan does, but the scale of the cuts proposed is at the margins of credibility. Other non-Trump candidates are offering even more fanciful proposals for enormous tax cuts. I haven't heard anyone proposing any moderate changes like taking the top rate back to 35%, where it was under GW Bush.

Krugman offers an explanation for the positions on taxes: the candidates are doing what rich people (ie, big donors) want. I think there are several things wrong with this explanation. This first is that according to a paper by Benjamin Page, Larry Bartels, and Jason Seawright on the policy preferences of the wealthy, people with high incomes are not demanding big tax cuts. The mean preferred top marginal rate is 34%, lower than we have today but higher than Bush is proposing. The mean preferred estate tax is about what it is today for estates of ten million, and probably somewhat lower than it is today for estates of $100 million--but Bush is proposing to eliminate the estate tax. Also, 65% if the sample said they'd be willing to pay more in taxes to reduce the budget deficit. In general, the picture was that the average rich person was what used to be a mainstream conservative, along the lines of someone like Bob Dole. Their sample was just from the Chicago area, and I'm sure that rich people in some parts of the country tend to be more conservative, but I also expect that rich people in the Northeast and West coast are less conservative. The second, and the one I'll focus on in this post, is that "crankification" is present even among Republican opinion leaders who aren't running for office.

I'll take Ross Douthat as my example, since he's a conservative reformer who holds that the Republicans should be trying to help the middle and working classes. In an analysis of the Rubio-Lee tax proposal, he says that it doesn't "get within even distant hailing distance of being revenue neutral" and offers some ideas about what Republicans should do. His primary goal is to reduce "the tax burden on people struggling to stay in the middle." Since he's realistic, he says that means increasing taxes on someone else. Specifically, his ideal tax reform "would end up raising taxes on some of Thomas Piketty’s petits rentiers (the upper middle class, that is) while probably cutting them somewhat for the super rich." Piketty defines petits rentiers as people who get "substantial and even fairly large inheritances: 200,000 ... or even 2,000,000 euros." The obvious way to increase their taxes would be to radically reduce the estate tax exemption, which I'm pretty sure is not what Douthat wants to do. I think what happened was that he interpreted the term as "rent-seeking," or using political power to get special treatment or protection from competition. There's a long tradition, going back to Adam Smith, holding that a lot of inequality is the result of rent-seeking rather than the workings of the free market. That's what Douthat means by the "on the tax code’s pro-rentier bias": not that the tax code is biased in favor of people with savings, but that it's filled with breaks for "special interests." The obvious problem with his proposal, which he doesn't even address, is the assumption that the upper middle class benefits more from rent-seeking than the super-rich do. Who is more likely to succeed if he calls up his Senator to ask for a favor, me or Donald Trump?