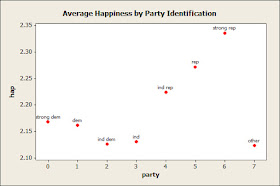

Since my series of posts on changes the relationship between political views and happiness trailed off into "something happened, but it's hard to say what it was," I wanted to do something that came to a definite conclusion. Arthur Brooks said "people at the extremes are happier than political moderates." He speculated that this was because "extremists have the whole world figured out, and sorted into good guys and bad guys. They have the security of knowing what’s wrong, and whom to fight." As you can see in this post, no such pattern is present in the GSS: average happiness increases as you go from left to right, except recently it's fallen off among people who say they are "extremely conservative." What if you look at happiness by party identification?

Now there is some pattern for strong identifiers to be happier (higher scores on the vertical axis). And since Democrats are more likely to be single, lower income, and less religious, controlling for those characteristics, as Brooks did, would make the pattern stronger. But what about the people who identify with another party? They're not a large group, even in the cumulative GSS, and are usually treated as missing values, but they are less happy than everyone except independents. And it seems likely that they are more "extreme" than any of the other groups--the two biggest enduring minor parties over the period have been the Libertarians and Greens. 14.7% of the "others" put themselves in one of the extreme ideological categories, higher than any other party group (11.3% of strong Republicans say they are extremely conservative and 1.0% say they are extremely liberal, for a total of 12.3%). And of course, there's a plausible explanation for why they would be less happy than Democrats or Republicans: they're dissatisfied with the way things are.

So it doesn't seem to be the case that extremists are happier than moderates. Rather, as I said a few posts ago, the pattern seems to be that people who are interested in politics are happier than people who aren't. Further evidence can be seen in the relationship with political views, people who answered "don't know" to the question on political ideology are the least happy group.

Brooks didn't give a link to his source, or any information about it, but if I were a betting man, I'd bet he did one of two things: (1) mixed up the patterns for party identification and ideology or (2) used a survey that counted "don't knows" on a liberal/conservative rating as moderates, which is sometimes done.

Saturday, October 31, 2015

Friday, October 30, 2015

What is to be explained?

In my last post, I said that the relationship between political views and happiness changed over time and that I'd have to think before offering an explanation. My general idea was that political polarization had been growing, so that there was an increasing tendency for people to be less happy when the "wrong" party was in power. The only problem was that there were signs of a growth in polarization in the 1990s, like the 1994 congressional election and the impeachment of Bill Clinton, so why wasn't anything visible then? In the hope of getting a hint, I estimated the relationship between self-rated ideology and happiness by year, and got this:

Higher values mean a tendency for conservatives to be relatively less satisfied. The zero value is arbitrary--it just represents the pattern in 2014. The 95% confidence intervals for the annual estimates are about plus or minus .02 (about plus or minus .03 in the first half of the period), so you could not reject the hypothesis that all the values within the Bush or Obama presidencies were the same. However, if you just look at the figure, it looks more like just random variation with a few exceptions--2004, 2008 and 2010.

So maybe the problem isn't to explain the patterns under recent presidents, but the patterns in a few particular years? The GSS is conducted in March, and March 2010 was when the Affordable Care Act was passed. So maybe that explains why conservatives (and especially "extremely conservative" people) were relatively unhappy then, but (maybe) not in 2012 and 2014. With G. W. Bush, the 2002 pattern wasn't unusual, but 2004-8 were. Those years had something in common--the United States was engaged in an extended war. It seems plausible that liberals and moderates would be more worried about war and its implications. The GSS started in 1972, but didn't include the question on political views until 1974, so being at war was a new event in the history of the available data (the first Gulf War took place in January/Feb 1991, but American troops were already leaving by March).

I'm not sure that what needs to be explained is a few unusual years rather than presidencies--the point is just that it's another way to look at it, and the data doesn't let us decide between the possibilities. This is a case where we start with what seems like a lot of data--50,000 cases--which turns out to be a lot less than we need for some purposes.

Higher values mean a tendency for conservatives to be relatively less satisfied. The zero value is arbitrary--it just represents the pattern in 2014. The 95% confidence intervals for the annual estimates are about plus or minus .02 (about plus or minus .03 in the first half of the period), so you could not reject the hypothesis that all the values within the Bush or Obama presidencies were the same. However, if you just look at the figure, it looks more like just random variation with a few exceptions--2004, 2008 and 2010.

So maybe the problem isn't to explain the patterns under recent presidents, but the patterns in a few particular years? The GSS is conducted in March, and March 2010 was when the Affordable Care Act was passed. So maybe that explains why conservatives (and especially "extremely conservative" people) were relatively unhappy then, but (maybe) not in 2012 and 2014. With G. W. Bush, the 2002 pattern wasn't unusual, but 2004-8 were. Those years had something in common--the United States was engaged in an extended war. It seems plausible that liberals and moderates would be more worried about war and its implications. The GSS started in 1972, but didn't include the question on political views until 1974, so being at war was a new event in the history of the available data (the first Gulf War took place in January/Feb 1991, but American troops were already leaving by March).

I'm not sure that what needs to be explained is a few unusual years rather than presidencies--the point is just that it's another way to look at it, and the data doesn't let us decide between the possibilities. This is a case where we start with what seems like a lot of data--50,000 cases--which turns out to be a lot less than we need for some purposes.

Friday, October 23, 2015

Lost Happiness

This post is inspired by Andrew Gelman's comment on a previous post about partisanship and satisfaction with various things. Andrew noted that the relationship between partisanship and general happiness had changed, a point first noticed by Jay Livingston, who was commenting on a piece by Arthur Brooks entitled "Conservatives are Happier, and Extremists are Happiest of All." Brooks said "the happiest Americans are those who say they are either 'extremely conservative' . . . or 'extremely liberal' (35 percent). Everyone else is less happy, with the nadir at dead-center 'moderate' . . . ." He didn't give a source, but Livingston noted that in the 2010 sample of the General Social Survey, people who called themselves "extremely conservative" were the least happy group.

I looked at the complete GSS data starting in 1972 to see how the relationship changed. If you look at the combined sample, there's absolutely no sign that "extremists" are happier: happiness increases pretty steadily as you go from left to right. Brooks said he had controlled for a number of other variables, so maybe that accounts for it. I doubt it, but I'm not going to pursue that issue.

Next I allowed the relationship to change from year to year, expecting that there would be some gradual trend--a tendency for conservatives to become relatively less happy. There was no sign of that, but I thought I saw some variation that corresponded to party of the president--conservatives were relatively unhappy when Democrats were in office. But on including a set of dummy variables for presidents, there was little variation until GW Bush and then Obama. So I ended up with a three-period classification: up to 2000, Bush (2002-8--the GSS is done only in even numbered years), and Obama (2010-4). The relationship in the three periods is shown in this figure:

Higher numbers on the vertical axis mean happier. In the 20th century, conservatives were happier than liberals, with those who called themselves extremely conservative being happiest of all. Under Bush, conservatives and extreme conservatives stayed about the same, but everyone else became less happy. Under Obama, conservatives and extreme conservatives became less happy, but everyone else stayed about the same. The net result was that happiness went down across the board between the 20th century and Obama. Liberals and moderates lost under Bush and didn't gain under Obama, and conservatives didn't gain under Bush and lost under Obama. There seems to have been an especially large drop-off among extreme conservatives, who became a lot less happy under Obama.

I was surprised at these results--I thought that even among people with strong political views happiness would be influenced overwhelmingly by personal circumstances, so that any relationship with the party of the president would be so small as to be undetectable. And if it is influenced by the party of the president, why just since GW Bush? People had strong feelings about at least some of the 20th-century presidents, notably Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton. So I'm going to have to think about this before proposing an explanation.

I looked at the complete GSS data starting in 1972 to see how the relationship changed. If you look at the combined sample, there's absolutely no sign that "extremists" are happier: happiness increases pretty steadily as you go from left to right. Brooks said he had controlled for a number of other variables, so maybe that accounts for it. I doubt it, but I'm not going to pursue that issue.

Next I allowed the relationship to change from year to year, expecting that there would be some gradual trend--a tendency for conservatives to become relatively less happy. There was no sign of that, but I thought I saw some variation that corresponded to party of the president--conservatives were relatively unhappy when Democrats were in office. But on including a set of dummy variables for presidents, there was little variation until GW Bush and then Obama. So I ended up with a three-period classification: up to 2000, Bush (2002-8--the GSS is done only in even numbered years), and Obama (2010-4). The relationship in the three periods is shown in this figure:

Higher numbers on the vertical axis mean happier. In the 20th century, conservatives were happier than liberals, with those who called themselves extremely conservative being happiest of all. Under Bush, conservatives and extreme conservatives stayed about the same, but everyone else became less happy. Under Obama, conservatives and extreme conservatives became less happy, but everyone else stayed about the same. The net result was that happiness went down across the board between the 20th century and Obama. Liberals and moderates lost under Bush and didn't gain under Obama, and conservatives didn't gain under Bush and lost under Obama. There seems to have been an especially large drop-off among extreme conservatives, who became a lot less happy under Obama.

I was surprised at these results--I thought that even among people with strong political views happiness would be influenced overwhelmingly by personal circumstances, so that any relationship with the party of the president would be so small as to be undetectable. And if it is influenced by the party of the president, why just since GW Bush? People had strong feelings about at least some of the 20th-century presidents, notably Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton. So I'm going to have to think about this before proposing an explanation.

Saturday, October 17, 2015

Miscellany

1. In a post earlier this month, we saw that people who were less satisfied with their financial situation were more likely to be Democrats. Common sense suggests that the relationship will differ depending on income. By and large, Democrats favor higher taxes and more spending on social programs, while Republicans favor lower taxes and spending. The higher your income, the more you benefit from low taxes and the less you lose from cuts in social programs. So a high-income person who's dissatisfied with their financial situation stands to improve it by voting Republican. I looked for an interaction using the Pew data, but there wasn't much evidence of one. While I did this, I had the feeling that I'd done this before, probably several times, with the same lack of results.

So to remind myself, I'll write this down: even among people with high incomes, dissatisfaction with your financial situation goes with more support for the Democrats. Of course, people have lots of reasons for choosing one party over another, so what if we look more specifically at opinions on redistribution?

The General Social Survey has a question "So far as you and your family are concerned, would you say that you are pretty well satisfied with your present financial situation, more or less satisfied, or not satisfied at all?" and one that asks them to place themselves on a 7-point scale going from "the government in Washington ought to reduce the income differences between the rich and the poor, perhaps by raising the taxes of wealthy families or by giving income assistance to the poor [to] . . . the government should not concern itself with reducing this income difference between the rich and the poor." If you regress the opinions on redistribution on financial satisfaction and income, the estimate for financial satisfaction is -.317 (a negative sign means dissatisfaction goes with support for redistribution). If you break that down by income level, that's -.367 for people with family incomes of under $40,000, -.245 for people between $40,000 and $90,000, and -.119 for people with incomes of $90,000 and above. The pattern implies that there's some value of income above which the relationship would change direction, but even in the highest income group distinguished by the GSS ($150,000 and up), dissatisfaction goes with more support for redistribution.

2. In a post from 2013, I remarked that Barry Goldwater had been left out in an account of how the Republicans lost black voters. Then last week I saw a piece by Andrew Rosenthal which said "The Republicans moved way past conservatism long ago. .... Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush, even Ronald Reagan would be apostates in this Republican Party." That is, Goldwater is lumped in with two relatively moderate Republican presidents. As I said in my post, the memory of Goldwater seems to have mellowed--people don't recall how extreme he was. I don't know well he'd get along personally with the Republicans in Congress today, but his politics would fit right in.

3. I ran across an obscure article by Robert Solow. Of course, Solow is anything but obscure--Nobel winner in economics, former president of the American Economic Association, etc.--but this article has been cited only twice according to Google Scholar (it was a brief contribution to a symposium in honor of another economist). It contains some comments on econometric modelling (and by extension, quantitative analysis in the social sciences) that I found interesting:

"For all our fancy talk about testing hypotheses and estimating structural parameters, I think that econometric modelling has actually made very little progress in doing those profound things. . . . Instead, I think, the main function of econometric modelling is rather to provide very sophisticated descriptive statistics." He did not mean this as a criticism: "The important thought I want to get across is that there is nothing undignified about econometrics as descriptive statistics rather than hypothesis-testing."

So to remind myself, I'll write this down: even among people with high incomes, dissatisfaction with your financial situation goes with more support for the Democrats. Of course, people have lots of reasons for choosing one party over another, so what if we look more specifically at opinions on redistribution?

The General Social Survey has a question "So far as you and your family are concerned, would you say that you are pretty well satisfied with your present financial situation, more or less satisfied, or not satisfied at all?" and one that asks them to place themselves on a 7-point scale going from "the government in Washington ought to reduce the income differences between the rich and the poor, perhaps by raising the taxes of wealthy families or by giving income assistance to the poor [to] . . . the government should not concern itself with reducing this income difference between the rich and the poor." If you regress the opinions on redistribution on financial satisfaction and income, the estimate for financial satisfaction is -.317 (a negative sign means dissatisfaction goes with support for redistribution). If you break that down by income level, that's -.367 for people with family incomes of under $40,000, -.245 for people between $40,000 and $90,000, and -.119 for people with incomes of $90,000 and above. The pattern implies that there's some value of income above which the relationship would change direction, but even in the highest income group distinguished by the GSS ($150,000 and up), dissatisfaction goes with more support for redistribution.

2. In a post from 2013, I remarked that Barry Goldwater had been left out in an account of how the Republicans lost black voters. Then last week I saw a piece by Andrew Rosenthal which said "The Republicans moved way past conservatism long ago. .... Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush, even Ronald Reagan would be apostates in this Republican Party." That is, Goldwater is lumped in with two relatively moderate Republican presidents. As I said in my post, the memory of Goldwater seems to have mellowed--people don't recall how extreme he was. I don't know well he'd get along personally with the Republicans in Congress today, but his politics would fit right in.

3. I ran across an obscure article by Robert Solow. Of course, Solow is anything but obscure--Nobel winner in economics, former president of the American Economic Association, etc.--but this article has been cited only twice according to Google Scholar (it was a brief contribution to a symposium in honor of another economist). It contains some comments on econometric modelling (and by extension, quantitative analysis in the social sciences) that I found interesting:

"For all our fancy talk about testing hypotheses and estimating structural parameters, I think that econometric modelling has actually made very little progress in doing those profound things. . . . Instead, I think, the main function of econometric modelling is rather to provide very sophisticated descriptive statistics." He did not mean this as a criticism: "The important thought I want to get across is that there is nothing undignified about econometrics as descriptive statistics rather than hypothesis-testing."

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

Partisanship and Happy Marriages

In my last post, I mentioned the claim that Republicans report having happier marriages than Democrats. I said it was basically true, but didn't give details, so here they are. The General Social Survey question is "Taking things all together, how would you describe your marriage? Would you say that your marriage is very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?" Partisanship is measured by seven categories; strong Democrat, Democrat, independent leaning Democratic, Independent, Independent leaning Republican, Republican, strong Republican. The question has been asked pretty regularly since 1973. Combining all years, the pattern is like this (higher numbers mean happier):

So (married) Republicans are happier with their marriages than (married) Democrats. People with stronger political affiliation are happier than those with weaker ones, with pure independents the least happy. I wouldn't call the differences large, but they are real (the F-statistic with 6df in the numerator is about 27).

Does this pattern change over time? Probably a little, but the general shape remains the same. I broke the data into three periods of roughly equal length:

The most noticeable difference is that average reported happiness with marriage was higher in the first period. The party differences on Democrat to Independent side may have changed a little, but nothing much is visible on the Independent to Republican side.

Why do these differences exist? My idea is that some people are more inclined to be satisfied with things, and they'll be attracted to the party of the status quo (see my previous post). As for why independents are the least happy, I think it's because people who are fatalistic or cynical are less likely to be happy with things, and many independents or weak partisans are fatalistic or cynical--that is, they're basically not interested.

Note: I just got a call from the Ben Carson presidential campaign. Maybe they figure that since I'm happy with my marriage, I'm a good prospect.

Thursday, October 8, 2015

Haven in a heartless world

A couple of months ago, the New York Times reported on some research by W. Bradford Wilcox saying that Republicans are happier with their marriages than Democrats are. It's a bit more complicated than that, because strong Democrats and Republicans report being happier with their marriages than independents or weak partisans, but basically the claim is correct. But neither the article nor the original research asked whether this relationship was specific to marriage or part of a more general tendency. To investigate this, I used a 2005 Pew survey that asked people how satisfied they were with ten different aspects of their life. I considered correlations with both self-rated ideology and partisanship (independents were closer to Democrats than Republicans, so I gave them a score 3/4 of the way between the partisans). I list the items by average correlation: a positive number means that Democrats/liberals are more dissatisfied.

Ideo Party

Household income .153 .211

Standard of living .140 .202

Happy with life .139 .187

Your job .111 .152

Housing .109 .117

Free time .078 .081

Relationship with spouse .081 .079

Family life .054 .096

Relationship with parents .047 .037

Relationship with children .026 .052

Liberals and Democrats tend to be less satisfied with everything. Beyond that, the items fall into two groups: those involving material things are more strongly associated with ideology and party, while those involving family and free time are less strongly associated. So although the claim reported in the article was correct, it was misleading because it suggested that liberals and Democrats were dissatisfied with family life in particular. In fact, you could interpret it in the opposite way: for liberals and Democrats, the family provides (partial) relief from the world outside.

[Data from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]

Ideo Party

Household income .153 .211

Standard of living .140 .202

Happy with life .139 .187

Your job .111 .152

Housing .109 .117

Free time .078 .081

Relationship with spouse .081 .079

Family life .054 .096

Relationship with parents .047 .037

Relationship with children .026 .052

Liberals and Democrats tend to be less satisfied with everything. Beyond that, the items fall into two groups: those involving material things are more strongly associated with ideology and party, while those involving family and free time are less strongly associated. So although the claim reported in the article was correct, it was misleading because it suggested that liberals and Democrats were dissatisfied with family life in particular. In fact, you could interpret it in the opposite way: for liberals and Democrats, the family provides (partial) relief from the world outside.

[Data from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research]

Saturday, October 3, 2015

More morals

The WVS also has questions about whether the following can ever be justified: "claiming government benefits to which you are not entitled," "avoiding a fare on public transport," "cheating on taxes," and "someone accepting a bribe." I wasn't going to write about those, but then Roger Cohen had a column in which he said that the Volkswagen emissions scandal reflected something about the German character. Specifically, "there is something peculiarly German about the chasm between professed moral rectitude and reckless wrongdoing." The WVS data, of course, are about what people say, not what they do, but that led me to wonder where Germans rank in "moral rectitude," which I would interpret as saying that breaking laws like those given above can never be justified.

I combined them into a scale and again plot it against the log of per-capita GDP (for those of you keeping score at home, it's based on the percent saying "never justifed" in each nation with weights from a principal component analysis). My expectation was that there would be two factors working in different directions. First, people in countries with higher levels of government corruption would be more likely to say that breaking those laws can be justified on the grounds that sometimes you have to. Second, more educated people would be less absolutist: they could imagine scenarios in which violating some rules would be justified. In general, more affluent countries have less governmental corruption and more educated populations.

Turkey is the biggest outlier, with very high rates of "never justified." It's the only predominantly Islamic country in the sample, which could be the explanation. If you put Turkey aside, then there is a tendency for people in more affluent nations to be more "absolutist." I could look up ratings for corruption, but my impression is that they would't correlate very highly with opinions. Germany is right in the middle on "professed moral rectitude." At the top are Turkey and Japan, with Italy (a surprise) in third, followed closely by Switzerland and the Netherlands.

I combined them into a scale and again plot it against the log of per-capita GDP (for those of you keeping score at home, it's based on the percent saying "never justifed" in each nation with weights from a principal component analysis). My expectation was that there would be two factors working in different directions. First, people in countries with higher levels of government corruption would be more likely to say that breaking those laws can be justified on the grounds that sometimes you have to. Second, more educated people would be less absolutist: they could imagine scenarios in which violating some rules would be justified. In general, more affluent countries have less governmental corruption and more educated populations.

Turkey is the biggest outlier, with very high rates of "never justified." It's the only predominantly Islamic country in the sample, which could be the explanation. If you put Turkey aside, then there is a tendency for people in more affluent nations to be more "absolutist." I could look up ratings for corruption, but my impression is that they would't correlate very highly with opinions. Germany is right in the middle on "professed moral rectitude." At the top are Turkey and Japan, with Italy (a surprise) in third, followed closely by Switzerland and the Netherlands.

Thursday, October 1, 2015

Morals

I concluded my last post by saying that Americans were relatively conservative on "moral" issues. This wasn't based on any specific piece of research, just an impression that I'd formed, so I did some more systematic analysis using the 2005-9 World Values Survey. The WVS has a series of questions about whether various things can "never be justified," "always be justified," or something in between. I constructed a scale based on opinions about homosexuality, prostitution, abortion, divorce, ending the life of an incurably ill person, and suicide. To limit the comparison to roughly similar nations, I used only nations in the OECD plus Taiwan. I show a scatterplot of scores (higher values mean more conservative) versus log of per-capita GDP.

As often happens, things are more complicated than I had remembered them. The United States is indeed conservative relative to its economic development (or something that's highly correlated with economic development, perhaps education), but it's not as exceptional as I'd thought. The biggest outlier is Italy. You could say that's because of the historical influence of the Catholic church, but Spain is also in the sample and it doesn't stand out at all. But for whatever reason, Italy stands out. Since my last post was an attempt to explain the nature of American conservatism, this suggests that if I'm right, there should be similarities to Italian conservatism. I know very little about recent Italian conservatism, but given the example of Silvio Berlusconi, I hope I'm wrong.

As often happens, things are more complicated than I had remembered them. The United States is indeed conservative relative to its economic development (or something that's highly correlated with economic development, perhaps education), but it's not as exceptional as I'd thought. The biggest outlier is Italy. You could say that's because of the historical influence of the Catholic church, but Spain is also in the sample and it doesn't stand out at all. But for whatever reason, Italy stands out. Since my last post was an attempt to explain the nature of American conservatism, this suggests that if I'm right, there should be similarities to Italian conservatism. I know very little about recent Italian conservatism, but given the example of Silvio Berlusconi, I hope I'm wrong.